English Writing for Scientists: Effective Use of Verb Tenses in Academic Papers

Content originally published on LinkedIn October 11, 2021

One of the main difficulties when writing a scientific paper in English

Verb tenses which mark when the action or actions in a sentence take place. Using verb tenses correctly in academic papers can be particularly confusing if English is not your native language—as the tenses you would use in your own language may not be the best choice. Different tenses are used for specific purposes, so they must be selected carefully. This can be challenging to native English speakers as well!

There are 12 basic verb tenses in English, and as many as 30 in total, but fear not—only three of them are extensively used in most academic papers. Before we discuss these, let’s review the basics.

A global look at the 12 basic English verb tenses

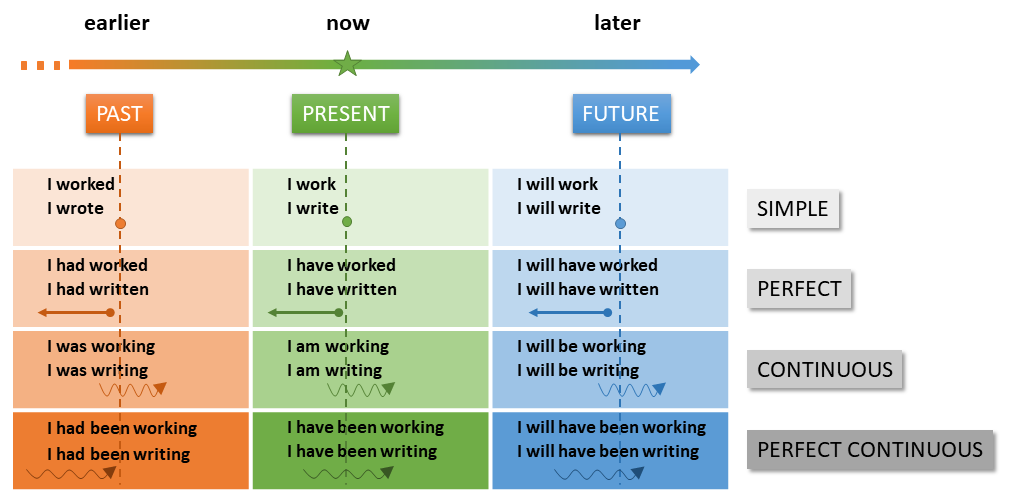

Tenses belong to three time categories: PAST, PRESENT and FUTURE. In English, each of these can take four main aspects: SIMPLE, PERFECT, CONTINUOUS (or PROGRESSIVE) and PERFECT CONTINUOUS. The resulting 12 tenses are summarized in the chart below, showing the basic structure for a regular verb (to work) and an irregular verb (to write).

Note that only two of the above tenses use the verb alone: simple past (I worked) and simple present (I work). All the others use auxiliary verbs as “helpers”.

Future tenses can be expressed with WILL:

I will work hard (tomorrow).

or with GOING TO:

They are going to work on this issue (at their next meeting).

Perfect tenses are formed using TO HAVE + past participle (ending in -ed for regular verbs):

I have worked on this project (earlier this month).

Continuous tenses use TO BE + present participle (ending in -ing):

I am working (right now).

Perfect continuous tenses combine TO HAVE + BEEN + present participle:

I have been working (since dawn/for the last hour).

The role of aspects

In short, SIMPLE tenses can be used for single actions, for established facts or for constant or repeated actions:

- My mother visited Paris last year.

- The sun shines.

- I study English; next month, I will read my textbook every day

PERFECT tenses denote a completed action that occurred earlier than the time of reference or that will be completed between now and a specific point in the future:

- He had finished his homework when the power went out.

- I have lost my notebook.

- I will have eaten dinner by then.

By contrast, CONTINUOUS refers to an action that’s in progress at a specific time. You can use continuous tenses to describe events that were ongoing in the past, often before another event occurred, for actions that are still ongoing, or for future actions expected to continue over some time:

- I was studying when you called.

- The professor is talking.

- This time next week, I will be taking my exams.

In general, the perfect aspect emphasizes the result of an action, whereas the continuous aspect emphasizes the action itself.

The PERFECT CONTINUOUS is used to describe actions that took some time but already ended, that started in the past and are still ongoing, or that will continue up to or beyond a specific point in the future:

- I had been walking fast and needed to catch my breath.

- I have been writing all day.

- I will have been living here for two years next month.

A detailed discussion of the various uses of each tense is beyond the scope of this article and can be found in this excellent article.

The three most common verb tenses in academic writing and when to use them

- The PRESENT SIMPLE tense:

Introducing a topic with a general statement:

The pancreas functions as both an exocrine and an endocrine gland.

Stating facts, generalizations, or what is already known:

Smoking increases the risk of lung cancer.

Making general conclusions about previous data:

These findings suggest that…

Citing a study without mentioning the researcher:

Rapamycin inhibits cell proliferation by blocking protein synthesis (Ref).

- The PAST SIMPLE tense:

Detailing the methods you used:

We collected blood samples…

Describing your results:

Exposure to this agent stimulated cell migration.

Citing findings made by others, when referring to a specific study:

In 2018, Smith reported that…

- The PRESENT PERFECT tense:

Referring to earlier but still relevant research in general terms:

Researchers have found that…; Several studies have indicated that…

Linking previous work to your own, especially to point out a gap in knowledge:

Although scientists have made great advances in this field, it is still unclear whether…

Describing your results:

We have identified a new pathway…

Drawing conclusions:

These findings have led us to conclude that…

Very few sentences in an academic paper will be written in the future tense. You should reserve it for perspectives—what you plan to do next to further your research.

When to use continuous tenses

Academic papers don’t often call for continuous verb tenses. You might still want to use them in some cases:

For referring to a body of work that has been building over time:

For the past three decades, evidence has been mounting…

For describing your research path:

We have been investigating this phenomenon since our initial discovery of…

Note the use of for and since in these two examples to introduce a period that began in the past and is still ongoing in the present. Both use the present continuous perfect tense. Clauses starting with since, for, and from as markers of time often call for a continuous tense, but the exact type will depend on when the events in question happen in relation to the present or to other events. This is one of the most confusing aspects of English writing, which deserves its own article.

Conclusion

Choosing the correct verb tenses in your scientific communications will make it easier for readers to understand your results and their significance. Some journals have specific guidelines on what tenses to use in different sections of a paper. Otherwise, using the three most common verb tenses as described above is a good place to start. When in doubt, follow the conventions used in articles published where you plan to submit your paper, or ask for advice from a colleague. And for best results, always keep in mind these key principles for better scientific writing.

This is part of a series of articles by Isabelle Berquin and Karen Tkaczyk, two trained scientists who moved into providing language services for scientists. Isabelle was a molecular biologist who worked in cancer research and Karen was a development chemist who worked in pharmaceuticals.

Karen provides editing services for scientists, mainly academics, who write in English when that is not their native language. Isabelle has co-authored over 30 research papers; she provides translation and consulting services for life scientists and enjoys turning data into engaging visuals.

Look out for the other posts in this series by both Karen and Isabelle. Topics include common mistakes authors often make, style matters, language variants, software tools that can help you edit your texts, tips for better scientific writing in English, and tips on creating impactful visual elements. If these articles are of interest or you’d like us to cover a specific topic, leave us a comment!

English Writing Tips for Scientists: List of Topics